A new interpretation of history

Many historians agree that the Macartney Embassy failed to achieve its goals, in part because of the ignorance of the Qing court in matters concerning the British. But Harrison's research shows that many Chinese people, especially those doing businesses with foreigners, were better informed than senior officials. The question she asks is: Why that knowledge did not reach the top decision-makers?

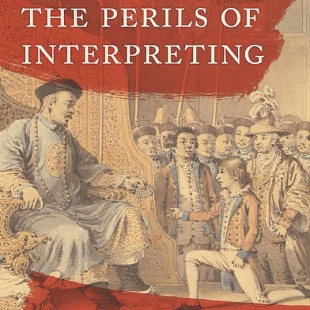

In the 274-page book, Harrison tells the unknown stories of the two interpreters to show how that ignorance developed-the repression of cultural mediators like Li and Staunton.

The Chinese who embraced both cultures were endangered by the growing tensions between China and Britain that culminated in the Opium Wars (1840-42 and 1856-60).

Li was born into a Catholic family in Liangzhou (today's Wuwei in Northwest China's Gansu province) in 1760.He left China for Naples, Italy, to train for the priesthood at the age of 11.

At the College of the Holy Family of Jesus Christ in Naples, also known as the Chinese College, Li outshone all of the other students. Gifted, hardworking, prudent, devout, wise, and always cheerful, Li excelled at Latin, a language mastered by men of the European elite at that time, and was good with people. His extraordinary ability in the language, and with people, made him the best choice to be an interpreter for the Macartney Embassy to China. He translated between Latin and Chinese.

George Thomas Staunton, 21 years younger than Li, received an education planned by his father George Staunton, who unconventionally believed that children had "aptitude for learning languages and science by observation and immersion".

When Thomas reached 11, his father only spoke to him in Latin. Taking his son around to see the latest scientific progress and inventions, as well as industrial development, when the elder Staunton joined Macartney on his mission to China, he also took Thomas. It took more than a year, crossing oceans, to reach China. On the ship, Thomas needed to study Chinese for three hours a day, so that when he met emperor Qianlong (1711-99), he could thank him in Chinese when receiving an embroidered silk purse.

In great detail, Harrison recounts the stories of the mission's journey to the emperor's summer retreat in Chengde, where they took part in the celebration of his 82nd birthday, and with whom and what they talked about, offering a glimpse into how powerful senior officials like Qianlong's favorite, Heshen, who was in charge of the empire's finances, gained knowledge about the outside world and how much they knew.

Li, wearing a wig and the embassy's uniform, interpreted for Macartney, but his role went beyond that. As a Chinese man who had lived in Europe for 20 years, he understood the cultures of both sides.

"In these early negotiations between China and Britain, the role of the interpreter was crucial. In both the Macartney and subsequent Amherst embassies, it was the interpreters who needed to explain what the other side wanted and helped find a solution," she says.

The Macartney Embassy failed, due in significant part to Macartney's refusal to kowtow and to follow the Chinese tribute system, so the emperor refused to initiate formal diplomatic relations with Britain.

However, Li effectively persuaded Macartney that the embassy had been a success and, alongside Changlin, the governor general of Guangdong and Guangxi, persuaded the British that a future embassy and further negotiations would bring dividends, Harrison says.

Knowledge is power. But in the world of early 19th century, the knowledge that linguists owned to interpret between different languages and cultures kept them at risk due to the question of trust.

Li even told his friend in a letter written in hiding after Macartney's mission was over, that he had never regretted undertaking something that "not even the most stupid person would have, if he had understood the danger".

During the following Amherst Embassy, the personal threat to George Thomas Staunton was a big part of the negotiations and ultimately one of the reasons that Amherst was unwilling to kowtow to Qianlong's successor, emperor Jiaqing (which he had been given permission to do before he set out from England), she says.

"It is always risky being an interpreter, because good interpreters have to really understand both sides of a negotiation. However, in early 19th century China, I argue that the two key problems were the expansion of the British Empire and the attempt by Qing officials to control interpreters as a way of controlling the British," she says.

Harrison devoted the other half of the book to the life of Li and George Thomas Staunton in the aftermath of the Macartney Embassy. Li secretly went back to China and became a priest who lived in hiding for the rest of his life, because he had lived overseas, which was not allowed in China at that time, and later, because of Jiaqing's policy against Christianity.

George Thomas Staunton continued to study Chinese, preparing for the next diplomatic mission. He later became a famous translator of Chinese and a banker during British trade with China, making a lot of Chinese friends when he worked for the East India Company in Canton, today's Guangzhou. However, he too had to flee, in his case back to Britain, when Jiaqing threatened him personally. He translated Ta Tsing Leu Lee (Qing Legal Code), becoming the first person that translated a Chinese document directly into English.