Jiangnan Spring probe should help plug loopholes in museum management

The National Cultural Heritage Administration and the Jiangsu provincial government's decision to launch an investigation into the management and handling of donated cultural relics at the Nanjing Museum is both timely and necessary, given the controversy over how the museum deals with donated collections.

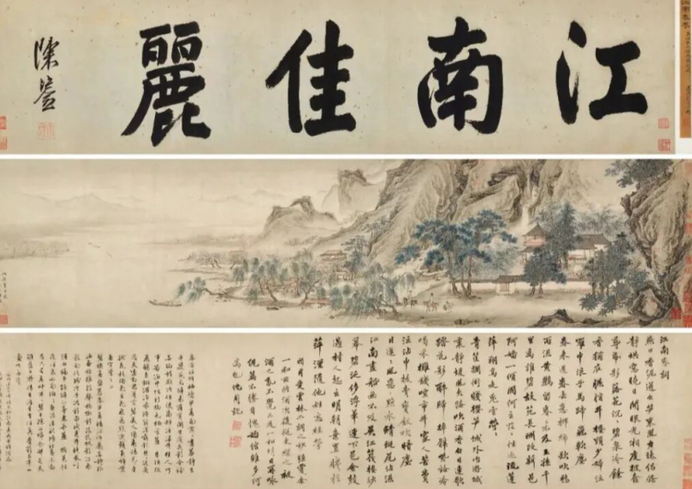

At the center of the controversy is Jiangnan Spring, a landscape painting long believed to have been done by Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) artist Qiu Ying and donated to the Nanjing Museum in the 1950s as part of a large gift from the descendants of renowned art collector Pang Laichen. It has come to light that a painting bearing the same title was recently up for auction in Beijing, understandably leading to questions about how a donated artwork from a public museum's collection can come up for auction, and whether there has been some impropriety.

Against this backdrop, it is reassuring that both the central cultural heritage authority and the Jiangsu provincial authorities have moved swiftly. The establishment of a special team dispatched to Nanjing, alongside a provincial-level investigation involving discipline inspection, supervisory, public security and cultural departments, signals that the matter is being treated with the seriousness it deserves. Such a coordinated effort also underscores the authorities' recognition that public trust in cultural institutions must be safeguarded.

Equally important is how the investigation is being conducted. It is hoped that the probe will proceed in a thorough, transparent and law-based manner. Only by clearly establishing what happened to the painting can the authorities allay public suspicions.

The Nanjing Museum has stated that Jiangnan Spring and four other paintings from the Pang family donation were deemed forgeries in the 1960s, removed from its inventory in 1997, and later allocated to a publicly owned cultural relic store, where a labeled copy was sold in 2001.Whether these procedures fully complied with regulations, whether donors or their descendants were adequately informed, and whether documentation and supervision were adequate are questions that require clear, authoritative answers. The promise by the provincial authorities to make the findings of the probe public in a timely manner is therefore particularly welcome.

Beyond resolving this specific dispute, the investigation should ensure that any loopholes or weaknesses in management and supervision are identified and systematically addressed. Lessons drawn from this case should help improve mechanisms across the country's museum system, ensuring that similar problems do not arise elsewhere. Preventing a repeat is just as important as determining responsibility.

This issue has emerged at a time when museums are enjoying unprecedented public popularity. As the central authorities emphasize the value of China's history and culture, museums have become vital spaces for public education and cultural confidence. Their credibility rests not only on the richness of their collections, but also on the integrity and professionalism of those managing them. Whether the handling of the Nanjing Museum case is fair, prompt and convincing will inevitably influence public perceptions about the public museum system.

At the most fundamental level, public museums are guardians of public assets. Donated cultural relics carry not only artistic and historical value, but also the trust and goodwill of donors and society at large. That trust must never be taken lightly. A transparent and credible investigation into the Nanjing Museum case will help reaffirm the principle that public museums exist to protect, preserve and pass on cultural heritage for the benefit of all, not allow it to slip into ambiguity or doubt.